H. Myers Stoneware of Baltimore, Maryland: A Research Retrospective

Twenty years ago, one of the great American stoneware mysteries was straightforward but elusive: Who had produced a somewhat large number of existing objects bearing the simple stamp, "H. MYERS"? Based on clay color and decoration, it was widely accepted that these were made in the Mid-Atlantic region; but with no satisfactory answer as to their maker, some of us particularly interested in Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia stoneware began to see this as a pressing research need. How this mystery was solved is a story I've never written about at length, but the recent consignment of one of my favorite pieces of American stoneware has provided an opportunity that seemed worth taking.

H. MYERS four-gallon stoneware water cooler with detailed incised game bird, part of our Spring 2024 auction.

Around the turn of this century, my brother, Luke, was working very hard on what became his award-winning history thesis at Johns Hopkins University on the subject of Baltimore's salt-glazed stoneware industry. Thanks to my parents' passion for Baltimore stoneware, Luke (like our other brother, Mark, and I) had grown up with Baltimore stoneware constantly around him. Almost none of it was signed by the maker, and a large portion of it was not even known to have originated in Baltimore. With relatively few exceptions, Baltimore stoneware was understood to have been obsessively decorated with some variant of a three-leafed clover motif, and almost all of it was made by one particular potter, a German immigrant named Peter Herrmann--at least, that was the collective mindset at the time. With now-commonplace attributions to important potters like David Parr, Henry Remmey, Maulden Perine and William Linton, it is hard to believe that this was ever the case, but it was. Why this has changed is almost entirely indebted to the thoughtful work Luke did twenty years ago.

Pitcher stamped "P. HERRMANN," made by Peter Herrmann in Baltimore around the middle of the 19th century.

Few Baltimore potters ever marked their ware, and this presented a problem. Entire bodies of work made over long periods of time in Baltimore were routinely given nebulous Pennsylvania or D.C. area attributions. When pieces were attributed to Baltimore, they were usually ascribed to the aforementioned Herrmann, simply because he was the only known Baltimore potter to obsessively stamp his work; these clover-decorated pieces of his then formed the basis for countless other incorrect "Herrmann" attributions.

Baltimore potters did favor this clover motif from around the middle of the 19th century onward, but prior to its widespread adoption, the dominant design tended to be a tulip-type motif with others distinctive to particular shops. Baltimore was the main Southern salt-glazed stoneware production center for decades and it boasted numerous potteries throughout the 19th century. For some reason, as it stood around the year 2000, most of their titanic body of work had collectively fallen into a black hole, with only that of Peter Herrmann withstanding the test of time.

Jar positively attributed to David Parr's Baltimore shop, one of the most influential in the history of the American stoneware craft. While almost no surviving work of Parr's was identifiable in the year 2000, through careful study Luke was able to conclusively establish which distinctive numerical gallonage stamps were used exclusively by him.

But back to the "H. MYERS" objects, this was one group of stoneware that Luke suspected was probably of Baltimore origin. It was clear that whoever was making at least some of them had exceptional skill, and this was one of the reasons why Luke, I and others felt that the story of these pieces was one very much worth pursuing. In fact, looking at the deftly incised water cooler above, it may now come as no surprise that Luke began to suspect that perhaps one particular master potter had a hand in the "H. MYERS" vessels: Henry Remmey, Sr., born in Manhattan around 1766. Remmey was about 46 years old when, after serious financial trouble, he decided to quit New York and take a job potting in Baltimore, where at times he produced some of the most beautiful American stoneware ever created.

Pitcher attributed to Henry Remmey, Sr. in Baltimore, circa 1820's.

One postulated origin of "H. MYERS" stoneware had been Philadelphia. It was around this time (specifically in 2002) that Phil Schaltenbrand published his excellent Big Ware Turners: The History and Manufacture of Pennsylvania Stoneware, 1720-1920. In it, he theorized just this:

The first man to burn stoneware in Philadelphia [after] Anthony Duche [the earliest Philadelphia stoneware maker] could have been Henry Myers. A potter named H. Myers worked in Baltimore in the 1780s and 1790s and before 1800 had possibly moved to Philadelphia ... . More information on this early stoneware maker will better explain what was happening in Philadelphia in the years following Duche's death. (Schaltenbrand, 7.)

This was certainly a theory worth considering, but Luke began to wonder if perhaps "H. MYERS" was not the name of a potter, but of a merchant for whom pottery was made. At the time, this was not generally understood to be as commonplace of an arrangement as it actually was amongst American potters and merchants, but one key fact stood out that seemed to point a way to an answer to this riddle: When Henry Remmey came to Baltimore, he did so to superintend the Baltimore Stone Ware Manufactory, owned at the time (1812) by a local china merchant named William Myers. We began to believe that perhaps Henry Remmey had made stoneware also for some other Myers family member, and indeed eventually William Myers' shop would devise to a nephew of his, Henry Myers, who took over the pottery and family merchant concerns in the fall of 1821. Everything seemed to be falling into place, but we lacked the hard documentary evidence to overcome reasonable doubts and previous theories. I recall this being frustrating, even more so when a piece of Baltimore stoneware popped up with a previously undocumented maker's mark.

Jar stamped "MYERS & BOKEE," Baltimore, 1834-1838.

The aforementioned Henry Myers was the proprietor of the Baltimore Stone Ware Manufactory for many years, from 1821 until 1838, but during the last four years of that run, Myers brought a partner into the business, another local merchant named John C. Bokee. The shocking discovery of a piece of stoneware stamped "MYERS & BOKEE" in the same manner as the "H. MYERS" objects seemed to finally prove once and for all just what was going on with these mysterious vessels. I again recall, however, frustration at the inability to find clear documentary evidence that what we had come to realize was true: That Henry Remmey--a man trained in a place considered to be the epicenter of the American craft, amongst some of the most skilled stoneware potters of the day--had come to Baltimore, completely transformed that city's stoneware industry, and in so doing left behind a large number of vessels stamped not with his own maker's mark, but that of the local merchant Henry Myers. To be sure, Remmey had left behind some vessels bearing a maker's mark of his: "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE." But so few of these existed that the paucity of Remmey's known work did very little to establish his reputation as one of the most important American stoneware potters, one who took Baltimore out of the dark ages of stoneware production and did very much to make it, as I said, the chief Southern salt-glazed stoneware production center. Proclaiming that the "H. MYERS" objects--not exactly obvious analogues to his "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" ones--were at least in many cases made by him was probably not sound research.

Remmey's "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" stamp. Previous to Luke's research, this was the only known maker's mark used by Henry Remmey. So few examples exist that Remmey's impact as a stoneware manufacturer was drastically underestimated.

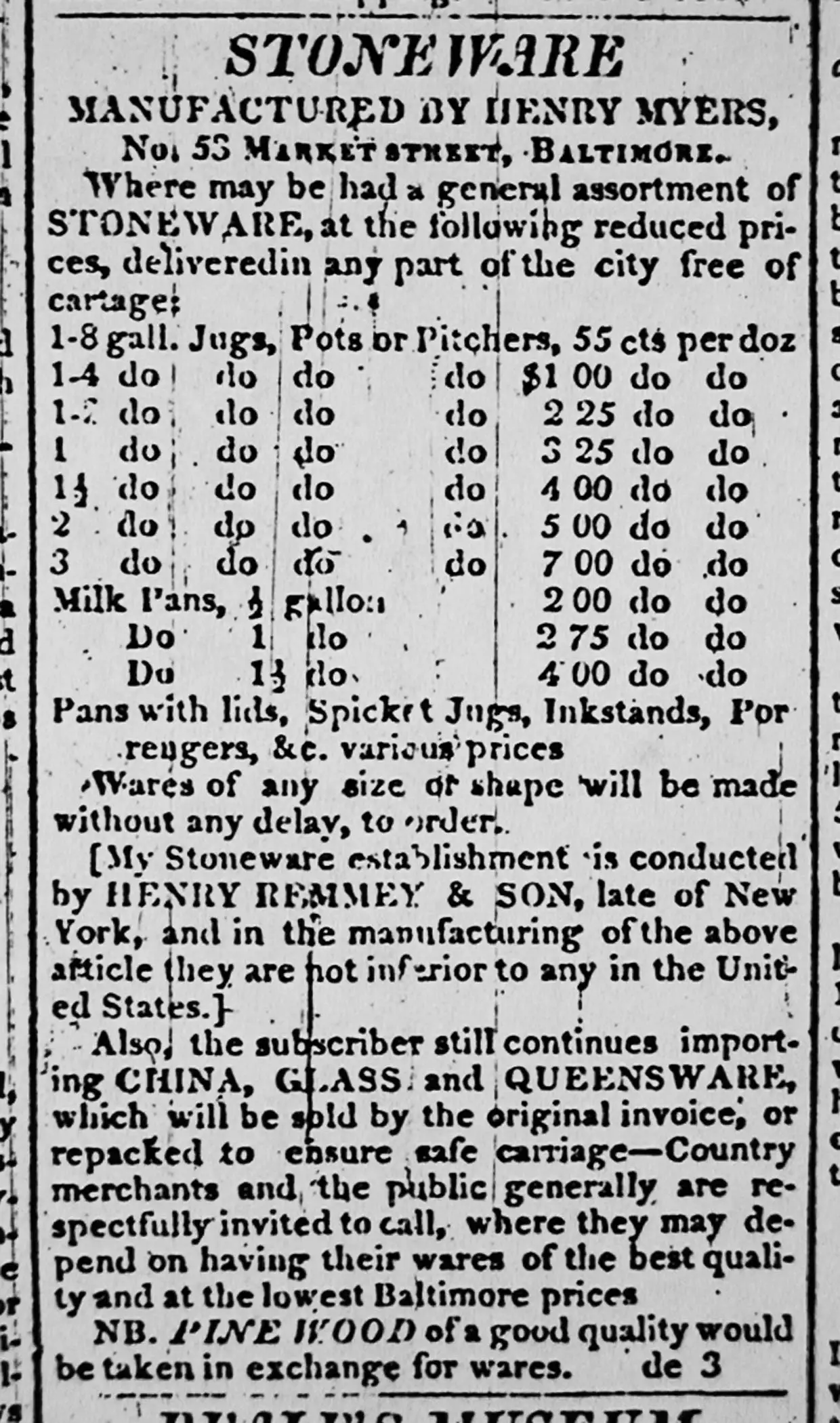

Rarely do these stories have such happy endings, but that ending did eventually come at the Maryland Historical Society. Luke had been spending day after day there, combing diligently through the city's period newspapers, looking for potters' advertisements. This was one of his main research paths, and it was extremely time-consuming. I try to remind people as much as I can that at one time not very long ago, the incisive research we can now perform from our smart phones through quick and easy internet searches was instead conducted manually, by hand, at various research repositories. (In many cases this still must be done.) Advertisements we actively sought twenty years ago only by dutifully cuing up microfilm reels and cranking through pages one at a time can be found today in a matter of minutes from our own homes. I received what was perhaps my first real taste of this kind of hard-fought sleuthing when I accompanied Luke on these research jaunts, as I sometimes did. I will never forget the day that we--after combing through page after page of 1820's Baltimore newspapers, sometimes successfully finding great tidbits about the Baltimore stoneware craft, sometimes not--found one of the most rewarding documents we have ever come across. Worded as clearly as it possibly could be, an 1823 advertisement for Henry Myers' manufactory announced the following to the public:

My Stoneware establishment is conducted by HENRY REMMEY & SON, late of New York, and in the manufacturing of the above article they are not inferior to any in the United States.

It is difficult to describe the feeling of satisfaction that comes with discoveries like this, and I suppose it's why I keep digging for new ones two decades later.

Henry Myers' ad announcing Henry Remmey & Son as the superintendents of his Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory. This ad ran for many months, this particular copy I believe coming from the July 3, 1823 issue of the American & Commercial Daily Advertiser.

In case you're wondering, Luke eventually turned this information into two groundbreaking articles, ones that helped completely reshape the collective understanding of the Baltimore stoneware industry and its place within the American craft as a whole. You can read these articles online:

Henry Remmey & son, Late of New York: A Rediscovery of a Master Potter's Lost Years in Ceramics in America 2004.

Baltimore Stoneware, in the Summer 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art.