Greensboro, PA Stoneware History: The Rumble Prohibition Stoneware

Our Summer 2024 auction will see the sale of one of the most historically important examples of Greensboro, Pennsylvania, stoneware to ever hit the auction block: The Rumble Prohibition Spaniel. Made in 1889 by a young potter for his brother, heavily inscribed on the bottom with the names of Greensboro pottery workers, this object's significance as a relic of both regional history and the American stoneware potter's craft is difficult to overstate.

The Rumble Prohibition Spaniel.

Greensboro, Pennsylvania, is the capital of southwestern Pennsylvania stoneware production, a place that set the pace in both style and scale of output for a distinct and beloved regional school of pottery. Titanic Greensboro shops like those of James Hamilton and Frank Hamilton & John Jones are quintessential ones to the American stoneware craft: Spaces where American workers took local clay, wrestled it with their bare hands into forms essential to the sustenance of their communities, then almost magically turned these fragile bodies of mud into timeless vessels of stone within the crucible of a lava-hot kiln. In so doing, they left behind utilitarian objects that are now frequently considered high-level examples of period American art, adorned with beautiful stenciled and freehand decorations particular to a very specific time and place.

Southwestern Pennsylvania stoneware pottery workers on the Monongahela River.

It is within this context that we find, in June of 1889, the Rumble brothers and their friends working at a stoneware shop in this small town on the Monongahela River. I think a lot about why pottery, and American stoneware specifically, seems to speak to people in a such a deep way. I think much of this has to do with a strong human connection with these inanimate objects. In one sense, I think we see something of ourselves in these pots, beautiful but fragile--often fleeting--creations made for a purpose. But I also think that in pieces of pottery we glimpse a piece of the potter. That is to say, the potter cannot help but leave behind some distinct trace of himself or herself, now intrinsic to the pot they bestowed to posterity.

In the case of the Greensboro pottery manufacturers, as is true for a large portion of the American stoneware industry, these potters often had their hand in literally every step of the production process, from dug clay to shiny warm pot extracted from the kiln. It is this extremely human aspect of American stoneware that I believe is ever-present in our minds as we collect and study it, and some examples communicate this humanity more than others. In the case of the Rumble spaniel, I can think of no other American stoneware object that does it so obviously.

Close-up of the front inscription on the Rumble spaniel: "R.H. Rumble / Greensboro / Greene Co., Pa."

In this tremendous creation we see the bond of brothers; the camaraderie of the stoneware shop; and the spirit of protest all communicated on an object meant first and foremost to elicit joy. In its form and decoration the Rumble spaniel takes its cues from the time and place in which it was fashioned: a swag- and dot-decorated seated dog figure that, while very rare, has come to be looked upon as something of a pinnacle of ceramic form for the region. On its front is emblazoned the following inscription: "R.H. Rumble / Greensboro / Greene Co., Pa," referring to Robert H. Rumble (born 1870), the son of John A. Rumble (1847-1940), a Greensboro stoneware potter. (Collectors of southwestern Pennsylvania stoneware will be familiar with the Rumble family. A 1960's interview with John A. Rumble's cousin Larry Rumble appears, for instance, at the end of Big Ware Turners.)

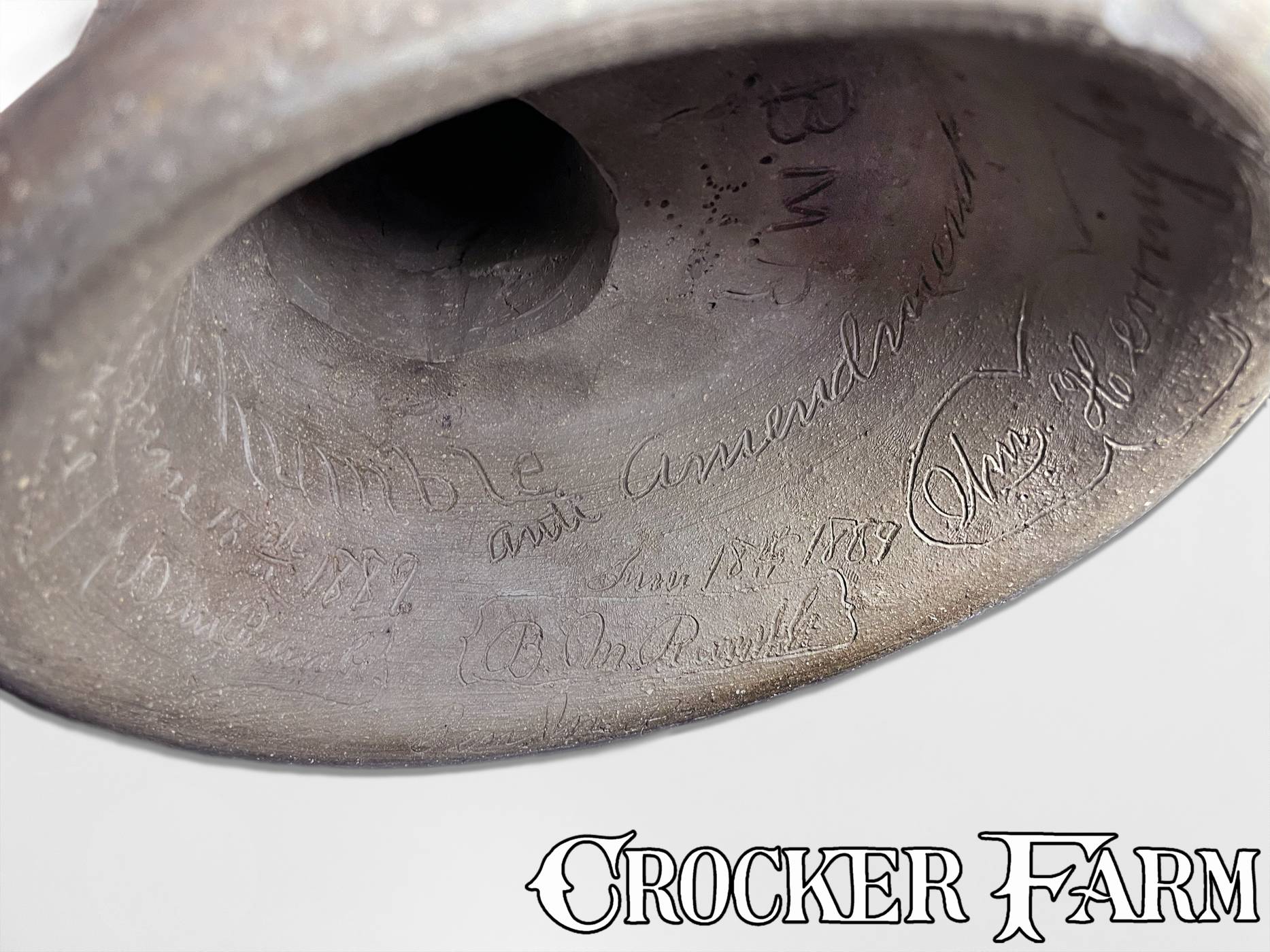

The underside of the spaniel is heavily inscribed, but one thing is primarily made plain: That it was made by Benjamin M. Rumble (born 1869), Robert's older brother. In the center of the bottom we have the initials "B.M.R." above the dotted letters "MR" for "Maker." Elsewhere we find "B.M. Rumble" and "Ben M.R." Because the 1890 federal census was almost entirely destroyed by fire in the 1920's, we cannot look up Robert and Ben in that year's census to find them making stoneware, but each of their death records describe them as potters. (More on this later.)

The profuse inscriptions on the bottom of the spaniel.

The Rumble brothers are not the only pottery workers whose names appear on the bottom of the dog. Indeed, we find six more, listed here with biographical snippets:

"Dan Rumble" (1870-1945). A cousin of John A. Rumble, Daniel Rumble appears as a worker in a "Stoneware Shop" in the 1880 census, when only nine years old.

"Wm. Herrington" (1868-1928). William [Delbert] Herrington is listed as a potter in Greensboro in the 1900 federal census.

"J. Couch". Brothers John (born circa 1859) and James (born circa 1868) Couch are listed in the 1880 census as workers in a "Stoneware Shop"; the same was said of their father, William Couch, and brothers Marion, Nathan and Hallick.

"F. Clevenger" (1866-1940). Frank [Lincoln] Cleavenger appears as a close neighbor of the Couch family in the 1880 census, listed as a 13-year-old worker in a "Stoneware Shop." Cleavenger is documented in modern sources as a long-time pottery worker in Greensboro and New Geneva. See, for instance, Phil Schaltenbrand's Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania, 2, 91, 95, 98, 105, 114, 156.

"F. Neil". Probably the Frank Neil (c. 1864 - 1943) who appears in the 1900 federal census as a day laborer in Greensboro; in the 1880 census he was living in adjacent Monongahela Township, next door to a potter named Charles Woherton.

"Isam Wilson" (1871-1919). Isham Wilson appears in the 1880 federal census as a boy living in Greensboro in the household of his father, a woodcutter. This dog appears to be the only document of his time as a pottery worker.

"anti Amendment" with the date June 18, 1889.

Besides the spirit of gift-giving, there was a message behind this spaniel: Each of these men was apparently a staunch opponent of a legislative program to bring prohibition of alcohol to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Raised in the home of the Whiskey Rebellion and steeped in an industry that went hand-in-hand with the keeping and distribution of liquor, it is no wonder these men probably saw this issue as something close to a life and death struggle. And so we find on the bottom of the dog the following inscriptions: "anti Amendment," "185000," and "June 18th 1889."

![The prohibition vote in the June 19, 1889 issue of The Pittsburg[h] Dispatch](/news/images/Pittsburgh-Prohibition.jpg)

From the lead article in the June 19, 1889 issue of The Pittsburg[h] Dispatch.

That date, the day of the fateful vote, came as the culmination of a long-term campaign by a group of Republican state legislators who were dead-set on bringing the amendment to a state-wide vote, in keeping with a general national push by temperance groups who had seen some success in other states. (The lead article in The Pittsburgh Post that day began with the following: "This is the day when the fate of gin fizz and his many liquid relatives will be decided.") To the jubilance of the Rumble brothers and their friends, the state-wide referendum saw the defeat of the proposed amendment with a total of 189,056 votes against it (at least according to The Pittsburgh Dispatch two days later)--just north of the 185,000 figure the Greensboro potters carved into the dog.

While we sometimes see potters subversively poking fun at the Temperance Movement (see, for instance, the work of the Kirkpatrick Brothers at Anna Pottery in Illinois), rarely do we see such an unabashed declaration that temperance (in this case, enforced by the government) is something to be defeated at all costs. The solidarity of these young men--perhaps none older than 25 years--both in their political conviction and their unity as coworkers projects a spirit of camaraderie forged in the American stoneware shop perhaps not seen on any other surviving object. The poignance of this object is underscored by the sad fates of Robert and Benjamin Rumble. Each tragically died young, succumbing to consumption a few years after the spaniel was created: Robert on May 20 or 21, 1893 and Benjamin on July 31, 1894. They were only 22 and 25.

The Rumble Prohibition Spaniel ultimately stands as something of a monument to the American stoneware craft as a whole, steeped in the spirit of the day it was made, exuding the camaraderie of the bustling shops that bore the objects we now hold so dear.

Sources:

Federal Census Population Schedules.

Greene County, PA Death Register, 1893-1915, pg. 137. (Death records of the Robert and Benjamin Rumble.)

The Pittsburg[h] Dispatch, January 3, 1889; January 13, 1889; June 20, 1889.

The Pittsburgh Post, June 18, 1889.

The [Uniontown, PA] Morning Herald, October 25, 1940. (Frank Cleavenger death notice.)

Funeral card for "Henry Rumble," with May 20, 1893 death date, Monon Center Collection, Greene Connections: Greene County, Pennsylvania Archives Project. (Robert appears to have been generally referred to by his middle name, Henry.) Various death records for the other potters were also consulted.